- Darren Almond

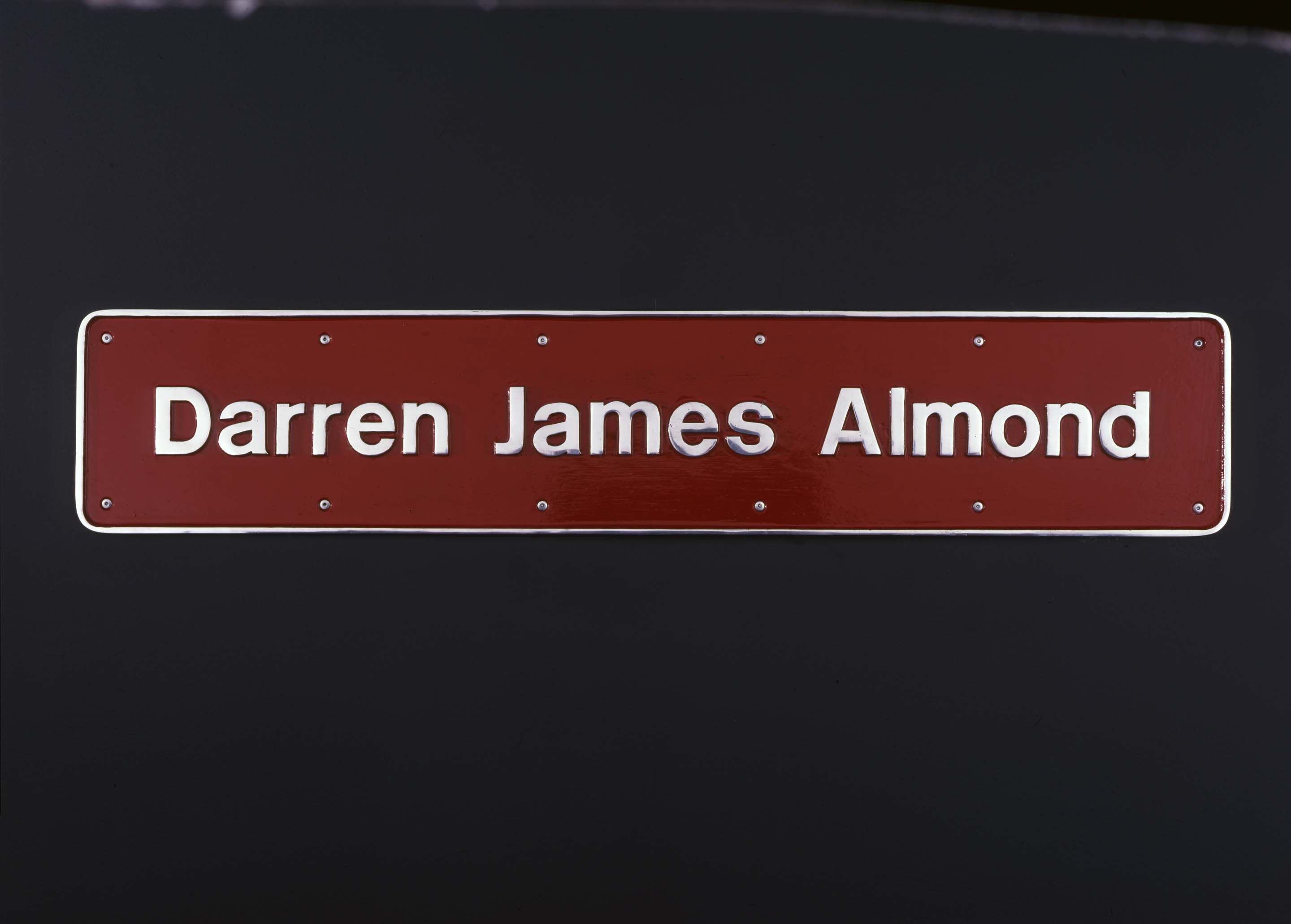

Darren Almond, Darren James Almond (Intercity 125), 1997.

Darren Almond, Darren James Almond (Intercity 125), 1997.

Darren Almond, Traction, 1999.

Darren Almond, Traction, 1999.

Darren Almond, Traction, 1999.

Darren Almond, Darren James Almond (Intercity 125), 1997.

Darren Almond, A Bigger Clock, 1997.

Darren Almond, Fan, 1999.

Summing up the work of British artist Darren Almond is difficult. He is a sculptor and a video artist whose work by all outward appearance, even when grouped by medium, remains incredibly disparate. What distinguishes it as a body of work, however, is his fascination with time. Time, whether addressed directly or indirectly, is the content of artists far too many to mention. As for Almond’s investigation into the subject, his work neither aspires toward the purity of mathematics nor the poetry of metaphysics. Instead, Almond aspires toward the existentialist mechanics of man-made time. It hardly matters if time is systematically differentiated into seconds, minutes, hours and days, or subjectively undifferentiated as in the process of waiting or forgetting.

The subject of Almond’s work -as monumental as the holocaust or as ineffable as boredom- all fall before the clock’s indifference whether the clock is as small as one found on a hotel nightstand or as large as the one we call history. According to Almond’s work, time is the ultimate institution whether it is captured through a video portrait of an inverted, floating train as in Schwebebahn (1995) or the sculptural works using digital clocks and ceiling fans or his real-time, live-feed videos - A Real Time Piece (1996) set in his vacated studio and H.M.P. Pentonville (1997) set in an empty prison cell.

For his exhibition at the Society, Almond will present a group of videos and sculptures from the past few years and will feature the debut of Traction, a new video work starring the artist’s parents. The title is a play on the two meanings of the word -to grip and to suspend one’s limbs following an injury. The video features an interview the artist conducted with his father while his mother listens in a separate setting. Son asks father: When was the first time you saw your own blood? This frightening question begins a recounting of Almond Senior’s injuries acquired through work and play, reflections that recall Sartre’s famous statement from Being and Nothingness that the body is not so much the place of being as it is the alienated property of being. With a thick, northern England, working-class brogue, Almond Senior relives each scar on his body as the site of an event, the body becoming a kind of geography. Traction is ultimately a mixture of tender mercies and hard knocks as tales involving breaks, fractures and missing teeth are transmitted from father to son while a mother listens at times astonished and at times amused. Although Almond Senior’s sounds like a hard life, Traction does little to undermine the life-as-game metaphor. The final impression is that it just happens to be one along the lines of a very harsh rugby match. After listening to Almond Senior it is not a question of whether there are winners or losers against the game-clock of life, but whether there are days when one ought to count oneself amongst the players or instead consider oneself the ball.