- Ree Morton: A Retrospective 1971-1977

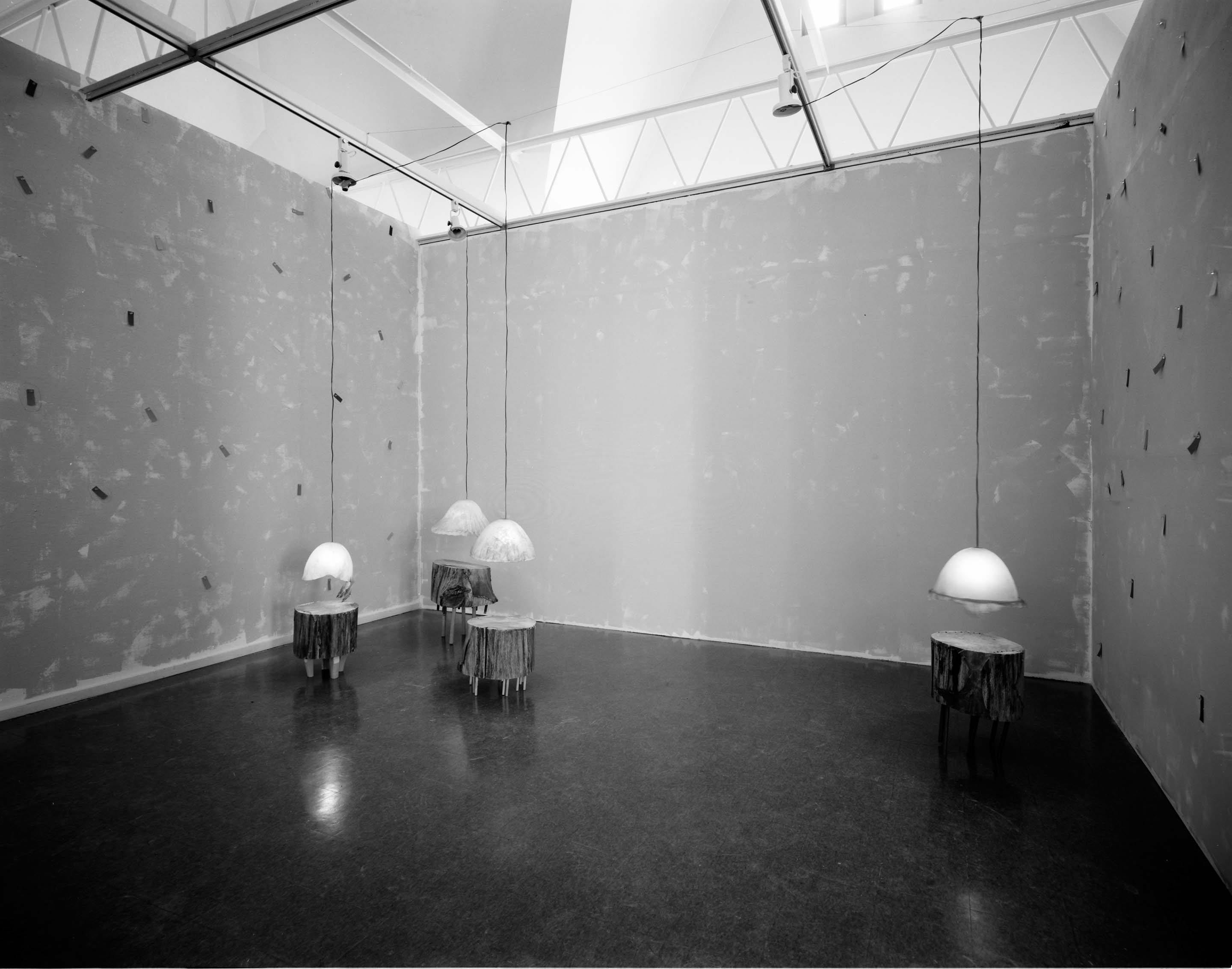

Ree Morton, A Retrospective 1971-1977, Installation View, 1981.

Ree Morton, A Retrospective 1971-1977, Installation View, 1981.

Ree Morton, Installation View. Left Wall: The Plant that Heals May Also Poison, 1974, and Bozeman, Montana, 1974. Right Wall: Paintings and Objects, 1973.

Ree Morton, Sister Perpetua’s Lie, 1973.

Ree Morton, Signs of Love, 1976.

Ree Morton, To Each Concrete Man, 1974.

Ree Morton, Installation View. Left: Study for Regional Piece, 1976. Center: See-Saw, 1974. Right: Regional Piece (#3), 1976.

Ree Morton, A Retrospective 1971-1977, Installation View, 1981.

Ree Morton’s accidental death in 1977 brought an abrupt end to her promising career. Although making art for only 10 years, she left us with a substantial and influential body of work spanning diverse means of expression. Her intensely personal installations ignored the boundaries between media and explored form, emotion, and personal myth via painting, sculpture and narration.

Along with many paintings , constructions, and drawings, the exhibition includes three complex, large-scale installations which develop literary or narrative themes: Sister Perpetua’s Lie, 1973, first shown at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; Souvenir Piece, 1973, originally installed in Artists Space, New York; and To Each Concrete Man, 1974, one of her most mysterious, poetic, and hermetic works, formerly exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

In 1974 Morton began a long-term use of celastic, a malleable material, which she formed into various drapery-like shapes. These works combine sentimental verbal cliches with embossed flowers, ribbons, banners, and bows, all painted in bright festive colors.

The Regional Pieces, 1976, are a series of vertically paired oil paintings of “sunsets and seascapes,” made up of vast ocean vistas and counterpart paintings of close-up views of submerged fish, all “curtained” with celastic frames.

One of Morton’s most complex visual orchestrations is Signs of Love, 1976, a roccoco feast of celastic ladders, curtains, roses, swags, ribbons, and small paintings. In its dangerously saccharine theatrical presentation, Signs of Love both flaunts and celebrates the emotion.

At the time of her death, the artist was working with The Renaissance Society on a show of new work, which sadly never was realized.

This exhibit was organized by the New Museum, New York, and in addition to The Renaissance Society, travelled to the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas; University of Colorado Museum, Boulder, Colorado; Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, New York.